|

|

|

|

|

|

The Church committee sought the services of a young Manchester architect, E H Shellard. He had designed several new Churches in Lancashire and the Manchester area, and was well regarded. He accepted the commission at a total fee of £128 7s 0d.

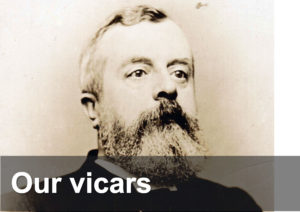

Edwin Hugh Shellard

Edwin Shellard was the architect who designed Holy Trinity Church. We have no likeness of him. He was born in Cheltenham on 8 February 1815 into what would today be regarded as a middle-class family. His father Joseph was a Surveyor of Roads and Joseph’s occupation was described as ‘Gentleman’ on Edwin’s own marriage certificate.

Shellard’s signature as it appears on the original plans for Holy Trinity Church, Waterhead.

In the late 1830’s Edwin was working from 4 Regent Street, Cheltenham at Baker and Shellard: Architects from where his first church design was accepted. This Church, St Philip and St James, Leckhampton was consecrated on 1 May 1840. The local press described the 850-seat church, saying ‘The whole has been well and spiritedly carried out, and reflects the greatest credit upon the well-known abilities of our highly talented and respected towns man, E H Shellard, Esq. architect &c. by whom it was designed and superintended’. This is quite an accolade for a 25-year-old.

At this distance of time it is not always possible to discover the reason for certain events but, by the early 1840’s, Edwin had relocated to the North of England and established his practice on King Street, Manchester and was making a name for himself as a designer of church buildings, which became the bulk of his work.

Most of his designs were in the early-English school of architecture. A look at his nearby churches such as St John Failsworth, St Mary Droylsden, or St Matthew Chadderton, reveal a certain ‘house style’ with some features being duplicated or perhaps just slightly tweaked.

Shellard married in 1850 and settled in Mottram where he attended St Michael’s Parish Church. There were no children. He died on 1 February 1885, just a week before his seventieth birthday. His widow installed a beautiful alabaster pulpit in the church in his memory.

Edwin Shellard’s career was relatively short at around 25 years but in that time he designed or enlarged/renovated at least 45 churches, many of which are still standing and are listed by English Heritage. An examination of them shows that he had an eye for a graceful line and detail which continues to delight and inspire the worship of God over 150 years later. Holy Trinity is a fine example of this.

The Gothic Revival was still popular at this time, so Shellard chose the Early-English style of the thirteenth-century to create a beautiful structure. It was said to be capable of accommodating 800 worshippers, in part owing to the capacious gallery running the entire length of the west end. In fact, 400 seems a more likely capacity.

The earliest known photograph of Holy Trinity Church, Waterhead. The photograph dates from after July 1857 when the wall encircling the burial ground was completed. The cottages to the right of the photograph were known locally as ‘Yellowstone Row’ and were demolished in the 1960s. The chimney on the far left, just visible behind the Church, is the Waterhead National School built in 1852.

Shellard chose an exterior of coursed squared rubble with ashlar dressings surmounted by a Welsh slate roof with ridge cresting. Entrance was achieved through a gabled south porch with shafts to its doorway, and with cornice and overhanging eaves.

Inside the Church, Shellard divided Waterhead’s long nave by buttresses from the two lean‐to aisles. Each nave arcade has six bays with clustered banded shafts and roll moulded capitals. Stumpy wall shafts carry a cambered truss and collar roof with king posts. All the walls and ceilings were gloriously painted; and much of the ceiling work still remains. At the front, shafts act as responds to the chancel arch which, from the very start, was decorated with a painted biblical text. Although Pevsner describes Waterhead Church as‘unadventurous when compared with his nearby St Thomas’ Lees,’ the local consensus considers the interior of Waterhead Church as superior.

Each of the nave windows — there are twelve in all — is a double-lancet with a quatrefoil above. Higher still are the trefoiled clerestory windows, one above each quatrefoil.

The only known image of the west-end gallery after its refurbishment in 1901, presumably after the removal of the organ.

The chancel and sanctuary at the eastern end of the Church are both lower in height. The windows are stepped lancets and an east window with continuous hood mould. There is a continuous sill band, and heavy unmoulded blocks between the windows and, possibly-unfinished corbel heads.

The cost of building Waterhead Church

Coins dating from the year of the Church’s foundation, 1847, when Victoria had been queen a mere 10 years. Left and middle: a gothic crown. Right: a penny.

Waterhead’s new church was expensive. Although the minister’s stipend was paid by Parliament, financing the erection of a new Church building was entirely the responsibility of its new Vicar, Revd Patrick Reynolds.

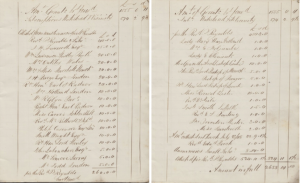

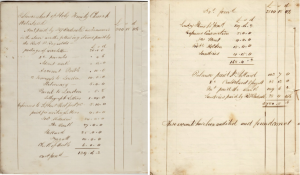

We know the cost of building Waterhead Church because this remarkable man kept a meticulous ledger detailing all the donations received. Reynolds wrote widely and was remarkably successful. The ledger reveals how he wrote 4,800 begging letters (at an additional cost of £20 0s 0d). A single page of his ledger — dated 1845, so only two years before the Church’s dedication — details support he received from Church luminaries such as His Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury, £10; the Lord Bishop of Manchester, £5; the Bishop of Bangor, £5; and the Rt Hon Lord Bishop of Leinster, £1.

Reynolds also wrote begging for money from non-clerics. He elicited funds from Lady Clements (£1); the Rt Hon Earl of Radnor (£25) and the Rt Hon Lord Stanley (£10). Local legend says he received £10 from the dowager Queen Adelaide. As a mark of the Queen’s known piety and modesty, she appears in the ledger in 1845 in an entry marked ‘A friend’—the only anonymous entry in the entire record.

The overall cost was prodigious. In an age when the average farm labourer earned about 18–20 pence a day, the concluding balance (undated but undoubtedly 1855) reveals a total cost of £3780 5s 6d. Of this huge amount, £1,380 came from church-building societies, and the remainder was collected from the inhabitants of Water head, Oldham, and beyond.

The cost did not just involve stone and labour. Reynolds’ ledger list the following items:–

- Postage of 4800 letters [from Revd Reynolds], £20 0s 0d

- 2 journeys to London, £10 0s 0d

- Lithograph letters, £5 0s 0d

- Shellard [the architect], £25 0s 0d and, later, a further £103 7s 0d.

Revd Reynolds’ own hand: pages from his ledger. Both pages date from 1845. In all, Reynolds wrote 4800 letters seeking financial assistance. These pages ably demonstrate the wide support Reynolds was able to elicit.

By any reckoning, Reynolds raised a colossal amount of money yet he was still short of the total required. Eventually, one of Waterhead’s main ‘cotton men’, T. G. Brideoake, cleared the residual debt with a donation of £880 5s 6d. The Church therefore opened without debt.

Reynold’s final accounts for building the Church is dated 1855. On the left-hand page, the third entry from the bottom reads simply ‘Shellard 25 . 0 . 0’ The second page shows the architect later received a further £103 7s 0d.

Firsts at Waterhead Church

The first religious service was its consecration on Trinity Sunday, 5 July 1847. It was conducted by the Rt Revd John Sumner, Bishop of Chester.

The first hymn was sung during this service of consecration. It was a now forgotten hymn by Isaac Watts, ‘Lord of the worlds above, how pleasant and how fair’.

The first baptism was performed by Revd Reynolds on Sunday 8 July, 1847: Thomas, son of John and Eliza Mayall.

The first marriage was solemnised by Revd Reynolds on 26 July, 1847, between Benjamin Stott, widower, and Mary Winterbottom, widow, of Waterloo Lane, Waterhead. Neither of the witnesses could write, and so each marked the register with a cross against which was written, ‘X his mark’— only men could witness a wedding in long-off 1847 because it was a legal ceremony.

The first burial was conducted by Revd Reynolds on 3 September, 1847, when Miles Cocker was buried. He lived in Waterhead and was aged 7 months.

The first Vicarage on Church Street (now named Church Street East) was completed on Monday 24 February 1857. This building was extended in 1870.

The first School Room was erected in 1868, but was enlarged in 1875.

The Church was first lighted with gas on Sunday 11 November 1870.

Many local people deplored the lack of a Church tower or spire — plans and foundations had been laid when the Church was first built. But Reynolds had another, more pressing, priority. Waterhead needed a school, so he appointed a planning committee in April 1851. This group immediately employed local architect Walter Tittensor. The new Waterhead National School opened in 1852 as a joint Day and Sunday School.

Today, the school’s foundation plaque resides in the comparatively modern Parish Hall (opened 1975). Old parish magazines show how the school received very good reports whenever the inspector called. For example, he could write at the end of the school’s first full year, ‘We have, at present, in the Sabbath School 450, in the daily [school] 250, and in the evening 100 young persons’.

Perhaps the only surviving photograph of Waterhead National School: aerial photograph taken in the 1960s before Daisy Hill Court and Rose Hill Court were built. The Institute is visible in the top right of the photograph.

Children assembled outside Waterhead National School. The photograph is undated but the costume suggests the mid to late Victorian era. The identity of the teacher is not known.

The northern elevation of Waterhead National School as seen from Waterworks Road. Copy of an undated photo (now lost).

Reynolds’ achievement becomes more astonishing when it is appreciated that he also helped found the daughter Church of St Thomas’ Moorside. He described the process many years later in a letter to the Church’s third Vicar, Gouldie French, dated 1886: ‘The Trustees of the dissenting chapel of Moorside gave me their place of worship. I had it licensed by the Bishop of Manchester, took duty therein every Sunday evening and presided over the day and Sunday schools till I left for Birmingham. It was this work that paved the way for the building of the Church schools and Vicarage of Moorside …’

As indicated, Revd Reynolds left Waterhead in 1854 for the Parish of St Stephen’s Newtown Row. He preached his final sermon on Sunday 15 October that year. Reynolds died in this new office in 1890.

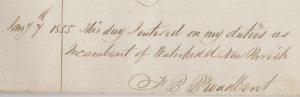

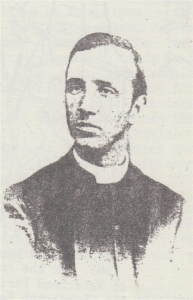

Revd Francis Buckley Broadbent (1855–1878)

Vicar Reynolds was replaced by the Revd Broadbent, who took office in early 1855. He made his mark immediately, for a new hand appears in Reynolds’ ledger below the last financial entry: ‘Jany 7th 1855 This day I entered on my duties as Incumbent of Waterhead New Parish. F B Broadbent’.

Holy Trinity Church, Waterhead – Francis Broadbent

Broadbent had been trained at the theological College of St Bees close to the Cumbria coast, which specialised in training its students as home missioners and clergy to the poor or heavily-industrialised areas. He soon demonstrated the effectiveness of that training. His first act was to convene the Annual Parish Meeting for Easter Monday, 9 April, at which the agenda mentioned ‘the desirability of a new font’. He commissioned a local stone mason, and the font was installed on Sunday 3 September that same year.

Next, Broadbent oversaw the enclosure of the graveyard, which had been used for burials for ten years, but remained open on all four sides. It was completed two years later in 1857.

He was also the Church’s first Vicar to have a Vicarage. As he explained in a letter dated 24 April 1871, ‘… for some years after I came to Waterhead I occupied a cottage such as those tenanted by factory operatives. It is impossible for me to collect funds for a parsonage. I purchased a plot of freehold land near the Church and built my present home upon it with private means; this house it is thought, with some additions and alterations would make a suitable parsonage house …’ The Church Commissioners bought this house from Broadbent in 1871 at a cost of £800.

Broadbent also formed an array of societies and groups. He founded the Waterhead Church and Schools’ Sick and Funeral Society on 22 April 1848, and the Sunday School and Congregational Library the following year, on 15 August 1849. He also imported into Oldham the tradition of the Whit Walk during his Incumbency.

A daughter Church: The St Ambrose Mission

By about 1870, Broadbent was becoming increasingly concerned for the wellbeing of poor children in the area of Littlemoor Lane in today’s Watersheddings. He found a suitable cottage, the exact location of which is now unknown. The cottage was soon full. In nearby Shrewsbury Street was a new day school for local children. Its founder was inspired by Broadbent’s work, and gave him the use of the building, rent free, for Sunday teaching. (A century later, the school relocated a few yards to become today’s Littlemoor Primary School.)

The building in which St Ambrose Mission began as a series of preaching meetings. The image comes from a brochure for Waterhead Church’s 1903 Flower Festival.

It was Waterhead’s third Vicar, Gouldie French, who first called the project ‘St Ambrose’ Mission’. While the Mission was clearly dedicated to St Ambrose of Milan (d. 397), the reasons for this unusual choice of patron remain unclear; it may be relevant that Waterhead’s Parishioners’ Sidesman at this time was one Ambrose Harrop.

Gouldie French sourced funds for a Curate-in-Charge to run the Mission. The first was David Dorrity, who was ordained specifically for such a role in 1883. He was clearly able, so was later inducted to a prestigious living as Rector of St Ann’s Church in Manchester, and yet later became an honorary Canon of Manchester Cathedral.

The Revd David Dorrity MA, Curate of Waterhead and Curate-in-Charge of the St Ambrose Mission.

A succession of Curates were soon building up the congregation, organising, teaching, and accumulating the necessary funds to build both the Church and a vicarage next door.

In 1907, the Bishop of Manchester appointed a commission to oversee and apportion the provision of Churches in East Oldham. In consequence, he proposed that a portion of St James’ Parish together with a portion of Waterhead parish were formed into a new district for the purpose of forming the new Parish of St Ambrose. Waterhead’s Curate, the Revd T C Holt, was to be its Curate-in-Charge. The corner stone of the new building was laid on 25 April 1908, and the Bishop of Manchester formally dedicated the building on 1 February 1909. The Mission was formally a Church while remaining a daughter church of Holy Trinity.

Falling attendance made inevitable the closure of St Ambrose Church in July 1999. It is now a pre-school and nursery.

St Ambrose Church in 1930. The image comes from Fred Lees’ book, ‘A short History of St Ambrose Church’.

Curates of Waterhead, with responsibility for St Ambrose Mission Church

- The Revd David Dorrity 1883–1887

- The Revd D H Griffiths 1887–1889

- The Revd G Tomlinson 1889–1891

- The Revd J Sidgreaves 1891–1893

- The Revd T Wortley Hodson 1893–1897

- The Revd A G Sykes 1898–1902

- The Revd F A Owen 1902–1905

- The Revd T C Holt 1906–1913

- The Revd J H Garnett 1913–1918

- The Revd F C Shirtcliffe 1918–1925

- The Revd J Wareing 1926–1929

- The Revd E Abel 1929–1930

Like his predecessor, Broadbent’s energy and foresight extended to the fabric of Waterhead Church. He wanted to expand on Shellard’s original vision since the Church had neither spire nor tower. So in 1869 he formed a committee under the chairmanship of Dr Leach. The Church had soon employed Thomas Cook of Mossley as its architect. A foundation stone was laid on Thursday 22 May 1873 but the work (under Messrs Geo. Mallalieu Bros. of Austerlands) progressed slowly owing to lack of funds. Torrential rain delayed the laying of the final stone but finally, at about 4 o’clock on Monday 18 September 1876, a stone measuring 3 feet and 6 inches was laid. Altogether, the height of the tower and spire was 123 feet and six inches at a total cost of £1,350. Above the pinnacle of the tower was a weathervane of copper weighing 70 lb and 8 ft 2 inches in height. It was yet another gift to the Church from Edward Mayall. (It was replaced in 1984 to commemorate the verger, Tom Dalton.)

Waterhead tower has a tall lower stage with clasping buttresses; and paired lancets above now light the base of the tower. The capacious paired bell chamber contains a single bell, and has lights in the upper stage, a corbel table and brooch spire with lucarnes.

At the same time as the erecting of the tower, a new west entrance was added through the base of the tower. Its substantial wooden door is single chamfered with a stone surround with shafts and deep moulding. This vast door remained the principal Church entrance until late in 2012 when it was bricked shut to make way for the new toilet block.

Having overseen the completion of the tower and spire, and started a new daughter Church, Broadbent died in office in 1878. He had been Vicar of Holy Trinity Church for 23 years.

The Revd James Gouldie French MA (1878–1926)

Gouldie French was the Church’s third Vicar and in some respects its greatest.

Appointing a man just short of 35 years of age was daring after so strong a predecessor as Broadbent. It was a wise choice, for he left it stronger than when he arrived and remained Holy Trinity’s Vicar for 48½ years.

‘Daddy’ French

John Gouldie French was born in Liverpool, and educated at Manchester Grammar School and Durham University, where he took his BA in 1869 and an MA in 1876. He was ordained a deacon in 1870 after teaching for a year in Halifax Grammar School.

French’s first curacy was at St James’ Church, Barry Street, on today’s A62, situated about 1½ miles closer to Oldham Town Centre than Waterhead Church. He was 27 years of age and

was given the task of establishing Christian classes for the poor of the Church’s neighbouring ward of Clarksfield. His preaching meetings met in a back room on Back Marsh Street, and were sufficiently successful to permit the creation of a self-supporting mission (or ‘daughter’) Church to St James’. St Barnabas’ Mission moved to the newly built Arundel Street in 1911 to become St Barnabas’ Mission Church in 1911. It became a Parish Church in its own right in 1932.

French was soon curate-in-charge of St Peter’s Church in Manchester in the period 1873–1876. The Church was demolished in 1903, but was situated in what is today’s St Peter Square near Deansgate, and very close to the site of the infamous Peterloo Massacre of 1819. French then served briefly as curate-in-charge of Hawkshaw near Bury (1877–1878).

The strength of Gouldie French’s achievements earned him the Incumbency of Waterhead. He was licensed in 1878 at the age of 35, and led his first service on 13 March that year.

Virtually the entire internal fabric of today’s Waterhead Church was completed during Gouldie French’s incumbency: he oversaw the relocation of some of the nave pews under the balcony (1883) after finding dry rot at the west end of the Church, the building of a new organ chamber (1905), the replacement of the pulpit (1905), major internal reordering (1906), and the addition of a much enlarged, gabled vestry (1911). He also oversaw building work at the Waterhead School when a new class-room block for teaching infants was added in (1881) at a cost of £661.

The internal reordering of 1905–6 included a new pulpit, altar, reredos, and choir pews, and redecoration of the chancel and sanctuary in the elaborate ‘William Morris’ style.

The first proposed reordering

Gouldie French’s plans for reordering the chancel were clearly in his mind many years before the actual project occurred, for in 1883 he commissioned the church architect H Cockbain of Middleton to explore different visions of the chancel. Almost none of these alterations were actually enacted, and even those which did come to fruition in the 1905 reordering were executed in a simpler, plainer style.

Looking east The simple altar installed by Reynolds has become a High Altar, which can be reached by climbing four steps. It has an elaborate reredos immediately behind it, with ornate stone work.

Gouldie French also proposed a vastly enlarged vestry (left) and an organ chamber (right), each with their own windows.

Looking south A capacious organ chamber has been installed, and a large number of pipes are visible through three large gothic arches. The steps to the left of the image lead to the new High Altar. Set into the wall beside the altar on the far left are two seats for servers; and two slender lancet windows now pierce the upper wall.

Looking north In this vision the Church has new clerestory windows: triple lancets rather than trefoils.

Two wide gothic arches with slender traceried pilasters (presumably of wood) look into the vestry; or they are ornamental, in which case the door-like structure is an optical illusion.

The small ‘cupboard’ to the right of the image, just above the steps, is likely to be an aumbry—a recessed cupboard in the wall near the altar used to store sacred vessels, and the reserved sacrament.

The earliest known photograph of the Church interior, presented in 1911 by a member of Vicar Broadbent’s family, to be hung in the new, enlarged vestry. The image is easily dated for the gas lights (introduced in 1870) are not yet fitted but the Church’s first pulpit has been adapted, which occurred in 1869. Also note the lack of an organ chamber, and the floor of the sanctuary has not yet been raised and decorated with encaustic tiles. Words are just discernible either side of the windows. On the left are written the Ten Commandments while on the right are Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. The ‘wire’ apparently running across the windows is in fact a scratch on the original photographic plate.

The Church interior in very early 1906. This is possibly the first photograph of the Church’s third pulpit of marble and alabaster which was installed in late 1905. The right-hand side of the photograph shows the nave-facing pipes of the new organ chamber, which was also installed in 1905. But the new altar and reredos are not yet in place, and they were introduced in 1906.

The finished result: the Church interior in about 1940. Note the extensive new stencil work on the walls and the newly installed reredos. The Ten Commandments, Creed and Lord’s Prayer are still visible. Notice also how the old gas-lights have been changed to accommodate electric light.

Gouldie French sponsored a wide array of societies and clubs for the betterment of his parishioners: Bible Reading Union; Church Defence Association; Church Missionary Society Parochial Association; Church Pastoral Aid Auxiliary; Communicants’ Union; Elocution Class; Teachers’ Preparation Class; and a Temperance Society.

He was also planning a new Church Institute for Holy Trinity. The postcard image above/below shows the pipedream image, which was first published in October 1909. A Church member, Mrs Hague, gave the site in March the following year and plans drawn up.

Something clearly went wrong as this building was never built. It probably cost too much so a different committee convened in May 1911, which planned a new, simpler building. It cost £650. The building was formally opened by Mrs Wakeham on 11 November. By mid-1912 Gouldie French could write, ‘we are glad to state that everything in connection with the Parish Hall and Institute is going on quite satisfactorily.’ By November 1913, the new Institute was finally open, for the Parish Magazine was advertising a Literary Society, a Billiards League, and several lectures in the new building.

A design for Waterhead’s new ‘Church Institute’ first published in 1909. An institute was built in 1912 to a simpler design. Curiously, the image of the Church in the background has no south porch.

Waterhead Church Institute in about 1970, after the demolition of Waterhead Congregational Church, which would have been on the wasteland on the right foreground. The design clearly reflects Gouldie French’s original vision, but is smaller and simpler.

Gouldie French championed many other causes: the Church soon sponsored the erection of Oldham’s first memorial to the Great War, on Heywood Street within sight of the Church, in 1920. Waterhead Scouts were also one of the first scout troops in the whole of Lancashire, founded in April 1911, about three years after the movement started nationally.

Possibly the last photo of Gouldie French before he left office in 1926: the Waterhead Scouts with Revd Gouldie French. Mrs French is seated to the Vicar’s left, wearing a flat-brimmed, square-topped hat.

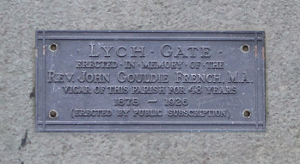

‘Daddy’ French was now growing infirm and, in his own words, ‘suffering from frailty and indifferent health’. In early 1926 he stated publically that he wished to reach fifty years in office, but fairly soon afterwards the era ended when he resigned owing to poor health. He was 76 years old. He died two years later on 4 June 1928, and was buried in the churchyard near Waterworks Road. To honour its colossus, the Church commissioned a memorial lych gate on Church Street East.

Lych gate

A lych gate (also spelled ‘lichgate’ or ‘lycugate’) is a gateway covered with a roof found at the entrance to a traditional English or English-style churchyard. It also appears as a single word lychgate. The word comes the Old English lic, ‘corpse’ because in pre-modern times a bier and coffin had to pass through it to enter the hallowed ground of the churchyard.

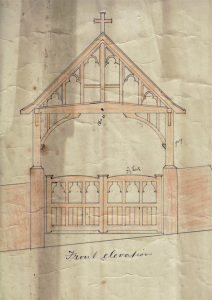

The original designs for Waterhead Church included no lych gate. Gouldie French first commissioned drawings for a memorial gate in 1920 to commemorate those who died in the Great War. The tendered cost was to be £280.

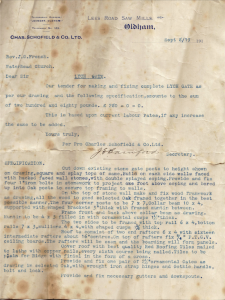

The lych gate was eventually built by Charles Schofield & Co of the Lees Road Saw Mill. The original quote of 1928 (for which Schofield forgot to complete the date) was reckoned at £280 0s 0d. The eventual cost was borne by public subscription, with a bronze plaque installed to the memory of Daddy French.

The lych was clearly built to a poor specification for quite quickly it lapsed into a state of poor repair. It was finally demolished in 2013 following a severe storm that weakened the roof struts beyond realistic preservation.

The Revd Ernest Briggs Moulding MA (1926–1933)

Holy Trinity Church, Waterhead – Reverend Moulding

Mr Ernest Briggs Moulding moved to Waterhead from Christ Church in Blackpool, and led his first service here on 13 March 1927. He soon resurrected the idea of a Lych Gate, in 1929, to honour his great predecessor following his death the previous year. The project was completed in early 1930 and officially unveiled soon afterwards on 30 May by the Archdeacon of Rochdale.

Moulding appears to have liked children and, in 1929, curtained off the north-west corner of the Church to create a children’s corner. This feature must have become decrepit over the years for it was completely reformed in 1966.

Revd E B Moulding’s Signature

Moulding left Waterhead to become Vicar of All Hallows in Bispham in Lancashire.

The Revd Edward Edmund Pearson (1933–1938)

Revd Edward Edmund Pearson signature

Mr Pearson was known as a kindly and happy man. He was also an inspiring and encouraging preacher which explains why his annual services to commemorate Armistice Day became so popular with ex-servicemen that extra seating had to be found for them.

Pearson died in office at the early age of 45, as a result of war wounds. He was buried in the Church grounds. The grave lies opposite the vestry door, within sight of the memorial plaque on the east wall of the church that commemorates the men of the Parish who gave their lives in the First World War.

The Revd Harold Walker (1938–1948)

Holy Trinity Church, Waterhead – Revd Harold Walker

Mr Walker was a keen musician and Church magazines suggest that he developed the choir. He was also responsible for repainting the Chancel with elaborate stencil work.

During his ministry, in 1945, a silver cross and oak credence were given to the Church in memory of a Church benefactor, Councillor Frederick Feber.

The Revd Leslie Howe (1948–1952)

He is still remembered as a tall and jovial man. He was also known as a keen player of snooker.

He is still remembered as a tall and jovial man. He was also known as a keen player of snooker.

Soon after his arrival, Mr Howe extended his predecessor’s choir and, for the first time, records indicate that women also sang in it. During his incumbency, wall-mounted gas heaters were installed into the Church in 1949 and the capacious west-end gallery was removed in 1951 after the discovery of dry rot. He was an able thinker and wrote many volumes on Christian philosophy, and was later awarded a doctorate of theology (TD) for this work.

Vicar Howe left Waterhead to join the Parish of St Aidan, Annfield Plane in County Durham. His last post before retiring was Rector of St Ebba, Ebchester, also in County Durham.

The Revd Raymond J Hunting (1953–1956)

Many in Waterhead village still remember Ray Hunting as a kind and self-effacing man.

Many in Waterhead village still remember Ray Hunting as a kind and self-effacing man.

Mr Hunting was soon worried at the physical state of the Church. He later wrote to his successor, Vicar Shaw, in 1958 saying, ‘One wonders how former incumbents could have been so indifferent to the deterioration [of the Church fabric] in their time. The appalling condition of the Church when I entered the living almost baffles description. Restoration is a long up-hill struggle.’

Mr Hunting was already an accomplished local historian, so it seemed natural that he should kickstart the Church’s second restoration project with a comprehensive history of Waterhead Church, with proceeds going toward a new fund. It was to be a social history as well as describing the fabric. He said, ‘There will be information about work in the mills and coal mines, features of everyday life, and details of local sporting ventures.’ In fact, it remains uncertain if he ever really started the work; certainly, it was never published and his detailed notes are now long lost.

After a brief tenure in Waterhead, Mr Hunting moved to become Vicar of Sileby in Leicestershire from where the photographhere derives. He wrote a series of short books about Sileby that are still in print.

The Rose Queen

Until recently, the enthronement of a Rose Queen was a high point in the social life of Lancashire Churches. Each participating church chose one of its younger members to become the Rose Queen for a year. The choice was often passionately contested, so an elaborate set of rules evolved: the Rose Queen had to have a track record of good church attendance, as did her extended family. Every Rose Queen had a retinue and the role of ‘Queen’s attendant’ was much sought-after.

The enthronement of a Rose Queen was always a spectacular affair and every church was keen to make its own Rose Queen the loveliest of all. Once chosen, the Rose Queen represented her Church at local events in other churches and raised considerable amounts of money for her own Church.

The origin of the Rose Queen is now obscure. It may have been an American variant on the ancient English custom of the May Queen. Waterhead’s first Rose Queen was introduced by its then Vicar, John Gouldie French, in the late Victorian era. He intended to use the idea as a means of attracting local families to the Church’s Temperance Society. It was also a way of raising money for the Church and giving the young girls in the congregation a chance to shine. There was also a Rose Bud Queen, for younger members.

The heyday of the Rose Queen was probably the 1950s, so many older members of our congregation remember the Rose Queens of those days with great affection. But the custom was fading in most parts of the North West by the 1980s. This corner of Lancashire remains one of the last places where the tradition survives. Today, it is virtually unknown elsewhere in England. Some Churches have recently started to elect a Rose King in order to preserve the tradition, with a modern approach to inclusivity!

The last Rose Queen at Waterhead Church was Rachel Donallon in 2005. The photographs show how elaborate the Rose Queen ceremonies could be, and the tradition was much loved at the height of its popularity.

The Revd Charles Edward Shaw (1957–1994)

Vicar Shaw’s time at Holy Trinity started badly for his wife Ada died within six months of his arrival. His long tenure was therefore often a time of great loneliness.

Vicar Shaw’s time at Holy Trinity started badly for his wife Ada died within six months of his arrival. His long tenure was therefore often a time of great loneliness.

Little was done to the Church building during Vicar Shaw’s time in Waterhead except the building of a new boiler house in 1969 to house an oil-fired heating system (it was converted to gas in 1991); and in 1984, the tip of the spire was found to be crumbling badly, so the apex stone was replaced. At the same time a new weather vane was installed as a gift from the much-loved verger, Tom Dalton. Also, to a design all of his own, he installed a speaking clock and placed it near the top of the tower. Instead of chimes, an amplified voice, synthesised and disembodied, floated across the slopes of Waterhead saying such phrases as, ‘It is now eight o’clock’. This clock secured Shaw’s local reputation for endearing eccentricity. It stopped soon after his death in 1994, and remains much missed in some quarters.

Many of Vicar Shaw’s passions centred on life outside the Church. He was a botanist of world-class stature and a Fellow of the Linnean Society (the world’s oldest active biological society, founded in London in 1788). His gift for finding rare plants in strange places such as rubbish tips became almost legendary, and his enthusiasm and wide-ranging knowledge helped inspire a generation of gardeners and botanists, including the well-known BBC broadcaster Roy Lancaster.

Vicar Shaw was a champion of local dialect, explaining why the local poet Harvey Kershaw of Rochdale wrote “The Parson o’ Waterhead” about him. This love of dialect helped inspire his affectation of a bluff Lancastrian exterior which hid a warm sense of humour and a gift for extravagant kindness.

With the opening of the new Parish Hall, the Church sold the old Institute to become a boys’ club. It was later demolished in the 1980s.

Like so many of the Church’s incumbents, Vicar Shaw died in office — and was the oldest to do so. He was 84. Only a week earlier he had driven to London to receive an MBE from Prince Charles as his reward for ‘services to the community’, for example organising meals on wheels. He is buried in the graveyard near the new boiler-house, and is commemorated by a magnificent memorial window located between the sanctuary and vestry.

Several changes occurred in the wider Waterhead Parish during Vicar Shaw’s incumbency. Perhaps the most important involved the school. The numbers of pupils at Waterhead National School were dropping fast, in large part because the 1946 Butler Education Act had taken so many powers from Church schools and built so many other ‘state’ schools. In 1900, the School taught about 200 children but only 32 were in the School by 1965. The 122-year history of the school ended in 1974 when Oldham Council compulsorily bought the School and demolished it to use the land for building the warden-care complex of Rose Hill Court. As part of the deal, the Council constructed a new purpose-built Parish Hall slightly up the hill, on Waterworks Road which was first used on 5 December 1974 but formally opened early the following year. It cost £31,000 — almost exactly ten times the original cost of the Church! Within a very short time, this new Hall was found to have been built to a poor quality and specification, and only now is it being renovated.

Revd Garry Whittaker (1995–2005)

Garry Whittaker was another Vicar with firsts: for example, he was the first Vicar of the new Millennium and the first Vicar to be known by his Christian name.

Garry Whittaker was another Vicar with firsts: for example, he was the first Vicar of the new Millennium and the first Vicar to be known by his Christian name.

Garry was an exceptionally capable preacher, which helps explain the major expansion in congregational numbers during his time in Oldham. No building works occurred during his tenancy, although he did oversee the Church’s 150th-anniversary celebrations.

Garry left Waterhead in January 2005, and is now Team Rector in the Bacup and Stacksteads Team Ministry.